|

click for

Left-Handed version

click for

Left-Handed version

It's all done with Mirrors.

A Diatonic Scale Mnemonic

by James Hollingsworth.

Thanks for your

interest in my discovery! It's

certainly not an invention. Simply

put, this is a way for guitarists to

remember the diatonic modes. The idea

appears to be original, I can't find

any reference to this beautiful

pattern having been discovered at any

time previously, though I saw ads on

youtube recently (2023) from a guitar

teacher who seemed to almost have the

repeating pattern.

But first, a short disclaimer. In the

course of explaining this "secret",

some of what I shall relate will seem

blindingly obvious. This is

intentional. Some will seem overly

sensational, even silly. This, is

intentional. The whole idea is to help

interested readers remember the modes.

This may now appear obvious. I hope

you'll bear with me because I wrote

this over 20 years ago :-)

If you want to skip the introductory story, go straight to the Mnemonic.

Once upon a time I taught myself guitar and this was the state of affairs for many years until I thought to myself, "Well, I'd like to know some things that I won't find out unless I ask someone...." These included esoteric matters including how to talk shop in a Jazz Band.

So, it just so happened that a friendly local market trader (from whom I bought my weekly supply of mushrooms) told me about this guy, and to cut a long story short, this same guy became, for a short time, my first and only 'official' guitar teacher.

He was wise in the ways of the fretboard and I picked his brains as best I could, between roll-up cigarettes, cups of (good) coffee, CD's by Larry Carlton, Bireli Lagrene and mad people who amplify their guitars full blast through Leslie speakers (which, incidently, sounds fantastic even via a Hi-Fi system).

Among the many

headachingly complex lessons I

learned such as why a F#7-9+15 chord

is so named and that sometimes

you've just have to accept that

there's no very good reason why a

minor 7th with flat fifth is called

a Half Diminished - it just is. [I'm

now informed that this actually

isn't true... "An m7b5 is a fully

diminished chord with a simple

flattened seventh, rather than a

double-flattened 7th (therefore,

only ‘half-‘diminished)". I told

you it was a headache.]

He also revealed to me the rather

disappointing 'truth' that if you

want to learn all those Diatonic

Jazz scales, you have to just play

them a lot until they finally get

lodged in your head.

"Hmmm...." I thought, and went away and played them.

A lot.

But, my mind doesn't work like that. I thought "I can handle the character of the Major (kind of cheerful), Minor (sort of sad) and Mixolydian (bluesy), but how can I get to grips with the characters if the others? What do they sound like? And apart from this, surely there must be a recognisable visual pattern in there somewhere."

And there is, I'm telling you.

When I found it, I thought "Someone must have discovered this already.

"But, really, this is just too obvious, this has got to be out there... it must be."

So I scoured the internet, and yet I found that no one even hinted at the existence of this amazing pattern that I thus concluded I had 'discovered'.

What this guy did for me was to bring together whole load of things that I already knew and showed me how they fit together. I had thought that modes were just to do with Plainsong, Gregorian Chants and Neo-Classical Fusion. But, no, they also turned out to be the language of exactly the kind of Jazz I was into at the time - Miles Davis in his Kind of Blue period.

The following will not be news to some, but here's a bit of background for the uninitiated. Originally, the modes were all variations of the same scale: you just start from a different degree of the root scale and go up eight notes, perhaps stopping on an interval that sounds pleasing when played with a drone. These days you can start with whatever note you want: the order of the notes in the scale is what matters.

most usefully speaking for guitarists, if you know the scales of these modes, it opens up the fretboard for both improvisation and composition - the same 8 notes in any diatonic octave are still available, but, for myself: while I knew these notes were dotted around the fretboard, my ability to navigate between known areas was limited to little patches where the scales I already knew were repeated. Sure, I could do a nice little run down the relative major while playing a minor key, hey, who can't, right? But, if you can get your head around modes, those little patches of illumination that you're limited to playing can become flooded with a light that promises to change your powers of musical expression unrecognisibly.

At least in theory, anyhow.

In practice, I couldn't say that knowing this stuff intellectually will have an instant impact on one's playing. Much of what most of us improvise in a 'solo' will be by ear anyway, and the idea of playing around patterns and scales never enters one's head because your fingers 'know' where the notes you want to play are. But in the long run, if you keep practicing scales, while playing a solo or while composing, those little prods of inspiration might suggest something like "Hey, why don't you go up two frets and play a section in the Dorian mode, just to see what happens?". This might make a magical relationship between notes that your style couldn't manage in first position become accessible to you, and before you know it, you've just played an original lick just by moving your accustomed habits to another pattern within the same key.

'Yeah, maybe." says my difficult imaginary reader, "So what's new?"

Moreover, perhaps on a more mundane level, practicing the modes will help your 'finger memory' to encompass hand positions and note sequences that might not otherwise occur to you. When your ear then suggests a novel melody, your digits will then be considerably more prepared to accomplish your daring feat of virtuosity.

so what did I do that made me move from the dull parrot fashion approach to something that turned me into some mad modal mnemonic evangelist?

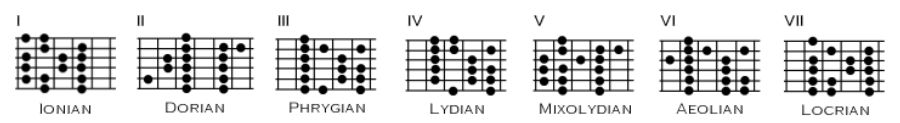

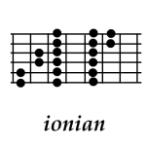

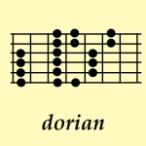

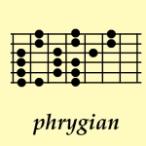

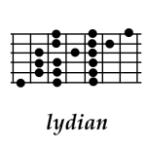

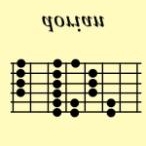

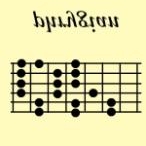

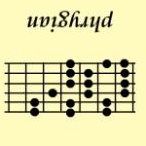

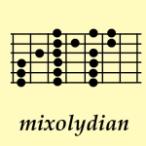

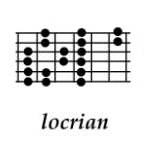

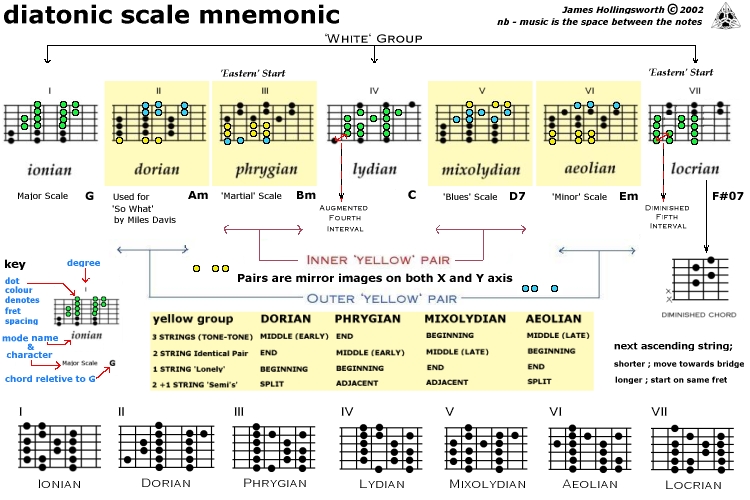

Well, I first converted the pictorial arrangement given to me by my knowledgable and skilled guitar teacher (Nick Reygate, Bristol (0117) 962 6043, very competitive rates, excellent coffee optional) into something more suited to my style. They originally looked liked this:

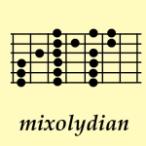

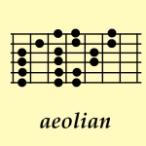

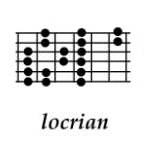

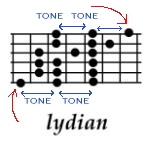

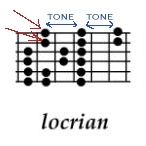

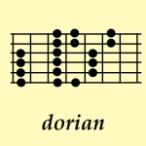

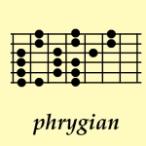

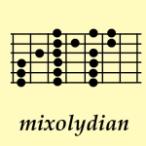

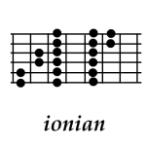

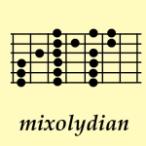

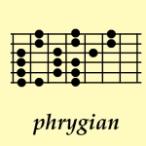

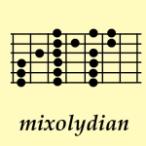

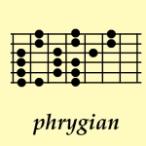

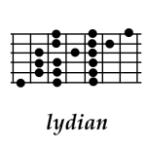

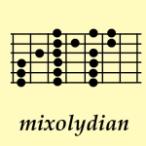

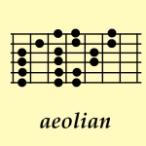

If you look, you can see some patterns already, such as with the Phrygian and Lydian, they're only slightly different, as are the Ionian and the Mixolydian. But still, I found it difficult to absorb the information "parrot-fashion". It has a 'sometimes-two-frets-per-string-sometimes-three-with-no-very-clear-pattern' arrangement (which I thought was a rather clumsy) so I changed this into a simple 'three-frets-per-string' arrangement, which enabled me to do the following:

- get further up the fretboard;

- add another three notes to the scale range (up to the 18th interval);

- play the scales more fluidly.

You might not find this to be the case...but hey, you can still play it the other way if you want, right?

OK. So, there I was staring at these dots, thinking "Hmmm...tone-tone, tone-tone, semitone-tone, semitone-tone, tone-semitone, tone-semitone" and so on and so on ad infinitum. Then, I put my guitar down and promptly forgot about modes for several weeks.

When I came back to it, fresh and with enough will to live to face all those dots without thinking "oh...what has all this got to do with music?" and I started seeing patterns. But I didn't go and have a lie-down...

the Mnemonic

This is where you should start paying attention, because everything I am about to say must be seen and observed, otherwise, the Table at the end is just going to look like a load of boxes with coloured dots arranged in an apparently meaningless (albeit, perhaps, rather artistic) fashion.

It might help to have a guitar handy, to try out my suggestions etc.

Once you've seen the pattern, don't force yourself to carry on reading, oh no not on my account. Go away and explore the scales, all you need is a print-out of the diagram.

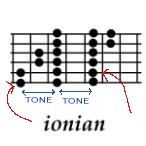

First of all, I noted that keeping to a strict three notes per string when playing a scale reveals three different arrangements in the way each string is fretted. These are:

TONE-TONE

SEMITONE-TONE

and

TONE-SEMITONE

(The shorter arrangements, containing semitones, I shall henceforth refer to as 'Semi's'.)

"Fine," I thought,

"and they're divided into two

groups". Below, I've represented

these groups by colouring them white

and yellow. Thus:

the white groups, above, are, you notice, conveniently placed at the beginning, the middle and the end of the seven modal scales in the octave. Of course, the eighth one can be ignored because it's just the same as the first.

"But", I hear you say, "there's three notes per string and you've only accounted for two of them with this TONE-TONE etc malarky. How do you know where to start on the next string? Eh? EH?"

Err...That's a good

question. But the answer is simple

enough. Basically, if you know what

the arrangement of the next string

is, i.e. TONE-TONE or SEMITONE-TONE

etc, then the following applies:

- TONE-TONE is

longer. Any string with a SEMITONE

is shorter;

- When ascending the scale the longer arrangement, TONE-TONE, takes up more space towards the bridge, and when descending, correspondingly more space towards the nut.

If you have a

shorter arrangement coming up, start

one fret towards the bridge, if it's

longer or the same length, then

start from the same fret as the

string you're playing on.

That's it.

It's easy. Isn't it?

"Alright", said Thrasymachus, "What about the blessed B string? That fouls up your scheme completely, doesn't it?".

OK, I admit, the B string would make it complicated if I had to keep referring to it all the time. But, basically, if you're at the stage in your playing where you want to learn about modes, then the B-string can most likely be taken as a given. You can handle it can't you? That's right, of course you can, you're used to coping with the fact that a guitar is tuned to the fourth above each successive string except for the B string aren't you? Absolutely. You're probably experimenting with alternative tunings, and these things go with the territory - what you really need to know is how to remember the patterns, not a 'by-rote' regurgitation of abstract structure, right? After all, this is about playing music, which is to do with sounds and emotions, not merely the tools we use to create those sounds. It's a means to an end. The B string? Phooey. You can't get way from it. Move up a fret like everyone else, Thrasymachus.

Who's Thrasymachus? He's the one standing at the back when Bill and Ted take Socrates away from ancient Greece.

Who are Bill and Ted? Someone's showing their age... is it me, or is it you? For further information please consult Einstein's Theory of Relativity.

Anyway. Please just accept the B string as an occupational hazard.

Now, what have all these white boxes got in common apart from being at the beginning, the middle and the end?

I'll tell you. In ascending order of pitch on each string (left to right as you look at the diagrams), they each have:

- 2 strings with even spacings of TONE-TONE

- 4 strings always arranged as two pairs in the following order

SEMITONE-TONE

SEMITONE-TONE

TONE-SEMITONE

TONE-SEMITONE

- both at

the beginning for the

Ionian;

- one at

each end for the Lydian;

- and both

at the end for the Locrian.

Look! Be amazed! See that the Ionian and Locrian patterns are an exact mirror image of each other! (well, using two mirrors they are)

Alright, alright! Settle down, settle down... But seriously, if you work backwards from the end of the Ionian diagram, the notes appear in the same relationship for each string as the notes progressing up the scale in the Locrian: TONE-TONE for the E-Strings, then TONE-TONE for the B and A strings, SEMITONE-TONE as you follow the descending pitch of the G and the ascending pitch of the D string and so on all the way to the opposite edges of the fretboard. The Lydian, being slap-bang in the middle is in an intermediate state with the 4 shorter arrangements being between the 2 longer arrangements.

It

looks

as if the scales are turning around

on an imaginary hub and balancing

themselves, according to the laws of

mathematics, between those

historically arbitrarily chosen

notes of the scale spread across

three points on each of the six

strings. Try and repeat that

sentence after a glass of whatever

you fancy.

Thank you to Rob Bray of The Straw Horses for the expression "Rotational Symmetry" - it describes what's going on here perfectly.

as a point of information, it's probable that the notes of the scale weren't really chosen arbitrarily. To be sure, those notes that coincide with a harmonic are there with good reason, but I'm just going to assume that the fretboard and the notes have already been invented without going into an explanation of the complex field of Acoustics. Thank you for your indulgence.

There is a pattern in there, but it takes just the right arrangement to make it obvious. In this case, it happens to be that the pattern becomes a perfectly self-reflecting if you play two and a half octaves on six strings playing 3 notes per string where the interval between strings is fourths.

Don't ask me why, but if you see this pattern, it sure makes it a heck of a lot easier to remember how to play the modes, even if you completely disregard the beautifully simple reference to the dynamically self-similar nature of the universe that it may present to your consciousness.

Well, what do you think so far? Neat maybe? Well, that's nothing, wait till you get your head round the other four modes. The yellow ones. They're unbelievable. Except there it is before your eyes: plain as a 4/4 rhythm.

the yellow group is a little more complicated, but that's only because there's more of them and the permutations of:

TONE-TONE

SEMITONE-TONE

and

TONE-SEMITONE

are correspondingly more various.

So here's another characteristic of these other four modes:

- they each have three strings with even spacings of TONE-TONE.

These TONE-TONE strings are always together!

"The central Lydian hub" do your eyes glaze over at this term? Before, you go away and think all this is far too complicated and I seem only to be revelling in the mere invention of new phrases, please understand that I'm simply trying to explain something that is observable. My wordplay is not gratuitous, I'm really am merely attempting to describe.

a complicated description of the blindingly obvious...

Skip this if you like. But at the risk of having to stifle a yawn - Bearing in mind that:

- because the Yellow Group has three strings always together with a predictable order (in contrast to the White Group which has four strings always together with a predictable order);

- because the Yellow Group is made up of four possible permutations of what, remember is the same scale for all the modes;

- being as we are restricted to the same actual order of notes (the difference between the modes depends on their starting point, remember);

- there is now the inevitable necessity that the remaining 3 strings have to have their shorter arrangements of SEMITONE-TONE or TONE-SEMITONE strings split up if we are to retain the integrity of the underlying scale.

more

simply put...

any string with

semitones in it might not be right

next to another string with

semitones in it.

This might not seem like such an astounding revelation but as long as it seems obvious, then I've drawn it to your attention.

more mirrors.

Anyway, this is

exactly what we find, furthermore,

these strings are arranged, yes you

guessed it, symmetrically - in a

mirror image of each other over the

whole scheme:

Yes, they do.

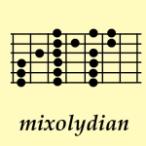

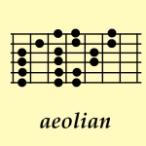

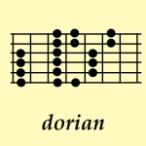

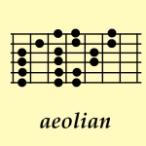

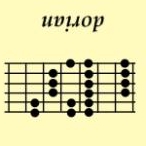

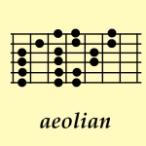

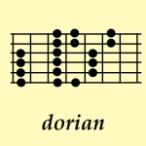

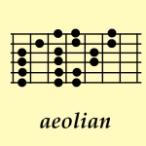

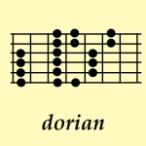

In the case of the two 'outer' yellow modes, the Dorian and Aeolian, we find the following...

Working ascending on the Dorian and descending on the Aeolian, the relationship on each successive string is:

- TONE-SEMITONE

3 strings of TONE-TONE

SEMITONE-TONE

SEMITONE-TONE

I expect the Aeolian

will be familiar to you as the

common (or garden) 'Minor' scale.

Bear this in mind, and you'll see

that if the Minor scale starts off

TONE-SEMITONE (which it does), then

the Dorian will have to end in the

opposite way round to this, which it

does, as SEMITONE-TONE.

So here's another couple of jigsaw pieces for the Yellow Group:

- There is a 'Lonely' string that's without an adjacent identical mate or a couple of spitting image pals (i.e. the yellow TONE-TONE's that come in 3 packs) This yellow loner is an individual - no other string has its blue-print in the same mode, and it's always a shorter arrangement (a 'Semi');

- The other 2 Semi's are identical twins and are Split from the 'Lonely' string in the Outer Pair and Adjacent to it in the Inner Pair.

let's apply this to

the Aeolian and the Dorian modes.

So what did we know before you started reading all this? Assume we know already that the Minor scale starts off TONE-SEMITONE (E string) followed again by TONE-SEMITONE (A string). It does doesn't it? Right, so far so good.

Now, let's say that I chip in some more information - Next is something simple to play, the bit you'll look forward to because you can whizz up and down it like nobody's business? OK, it's the 3 lovely TONE-TONE strings. There you go, you can do that, no problem, but where next? Well, you've reached the end of the scale, you're at the top of the second octave, you've reached the goal...or have you?

Music is more than a progression up and down scales isn't it? You want to do more than reach that octave, and anyway, the octave in a mode might just sound sublimely awful in the key you're actually playing in. So what do you do? Where do you go from there? Well, in the standard arrangement of notes for the six-string guitar, you have to start moving your hand up the fret board if you want some more space to move in, don't you? Not in this "New! Improved! Mnemonic", my friend. No, no. You can whip up to the next 3 notes easy as you like. Agh! If only you could remember what they were without toggling back to the mundane lowlands of playing-in-the-scale-of-the-key-of-the-piece.

But, wait! Where was I?

Oh yes. You've reached the end of the Aeolian scale, you're at the top of the second octave and you know that there's only one string to go before you run out of fingerboard...living on the edge...You also know that the scale started TONE-SEMITONE, TONE-SEMITONE and just add that bit of info about the Lonely string: well, that one string can't be the same as those two down the other end of the scale can it? No!

So, what do you do?

SEMITONE-TONE, that's what.

Simple.

but Beware. Continuing with the Aeolian, being a known quantity (it's your old acquaintance the Minor Scale after all), we can look at its Outer Yellow Pair counterpart, the Dorian. Now, there's a danger here. I know that what I'm suggesting is that these scales are mirror images of each other, but here's a warning for all those intrepid mode-vaulters out there who want to go straight from playing in the Aeolian mode to the Dorian in the twinkle of an eye... well, you might want to.

Read on...

The relationship between the Inner and Outer Yellow Pairs is symmetrical in that:

- the Dorian and the Aeolian start in the same way, yet contrastingly, the Inner pair in the yellow group (the Mixolydian and the Phrygian) don't start in the same way.

Note that the mirror image nature is based on both the Y axis and the X axis. Here's the danger I was talking about: the Dorian starts in the same way as the Aeolian, even though they're mirror images. The Inner yellow pair, as we shall see, do not start and end in the same way but they are still symmetrical on both axes. (note that this has a lot to do with where those TONE-TONE's are.)

This only emphasises the beauty of the scheme however, look at what happens if you flip the Dorian into the page top to bottom on the X axis:

... and then flip it on the Y axis left to right...(with a little adjustment for the blessed B String...) and you end up with the Aeolian!

Didn't expect that did you?

Now, that's a pattern isn't it? Rotational Symmetry, right there.

the Dorian - another line of reasoning. Why bother basing your idea of how the Dorian mode begins on the Aeolian particularly?

The Dorian happens to be in very close physical proximity to something else that's probably at least as familiar to you as the Aeolian is. Remember that the Dorian mode is only one TONE removed from the Ionian mode, otherwise known as your friendly 'Major' scale. Bearing this in mind, therefore, starting on the Dorian should be a piece of cake if you apply this knowledge that you already possess. Most people with a little musical knowledge will know what interval the 3rd note of the major scale is, so will have no trouble seeing that the second note of the Dorian mode is just the same.

So, given that the minor scale has those two similar TONE-SEMITONE's at the start, and, as we now see, the Dorian also starts TONE-SEMITONE, the only way to go after that is somewhere different to the Aeolian.

Trust me.

This means the A-string either goes TONE-TONE or SEMITONE-TONE.

Now, remember those jigsaw pieces above? The Lonely string principle? And that it's split from the twin Semi's in the Outer Pair? OK it's all plain sailing from here - you play TONE-TONE, TONE-TONE followed by, TONE-TONE. Zooom.

And finally? Well, the last two strings can't be the same as the first one, and you've played the TONE-SEMITONE string who's an individual, a discrete and independent unit (in fact this string might be quite happy as it is and not lonely at all - just 'free', but I'll call it lonely 'cause this description catches my imagination, and now I come to think of it, it's far too late to go back and rewrite every reference to its being 'Lonely' to being 'Free' instead. Oh, what a great thing is hindsight. Ho hum.). So the only way to play those two remaining strings is SEMITONE-TONE, SEMITONE-TONE.

Now, you might say, "You just explained about how the Aeolian ends in SEMITONE-TONE, and the Dorian begins and ends in the same way as the Aeolian, so if you remember that why do you have to think about this Lonely string business?"

Well, if you've just played the closing notes of the Aeolian, then this might seem obvious to you and fresh in your mind, but that is the Path of the Parrot.

the Path of the Pattern. In time, these things will become clear to you and you too may soon be able to make such leaps of photographic memory. But, basically, put into the picture of the whole scheme, who's going to remember a bunch of isolated facts that don't relate to each other? Such as, for example, that the Aeolian ends in a particular way? You might do, you might not. But my vote is that it's easier to remember how the Major and Minor scales start than it is to remember that the outer pair both end SEMITONE-TONE. Once you've got the basic principles of the pattern memorised, the modes all just obey these simple rules and the precise memorisation of the individual scales can come in its own time. Concentrate on where you are and how you got there. For the sake of explaining myself, I shall (perhaps rather vainly) call this 'The Path of the Pattern'.

On the other hand, if you can remember that the outer pair both end SEMITONE-TONE, then you've still got an important clue. The most valuable aspect of this mnemonic as an aid to memory is that as long as you remember something about one of the other scales in the group, then you've got a clue about how the one you're playing goes. This inter-relatedness is crucial to an integrated learning process and makes the pattern watertight, compact and digestible.

I hope.

Moving quickly on to compare the last two scales...

The Inner Yellow Pair differ from the other two in the yellow group in that:

- They start differently to each other;

- the TONE-TONE's don't split the Semi's up (the Lonely string has the similarly sized Twins for company);

- the TONE-TONE's are at opposite edges of the fretboard to its Inner pair counterpart.

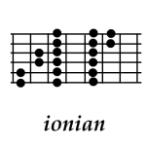

It's got a minor seventh.

That's it. No frills, no if's, no but's.

So what that means is that instead of playing:

this:

you play the seventh

differently- just flattened,

thus:

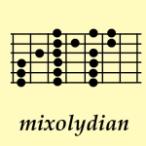

So, knowing that the Ionian begins TONE-TONE, TONE-TONE bringing us right up to the D string, where the octave is, what we're left with is only one candidate for the "I've got my 3 strings arranged in a TONE-TONE formation altogether at my front end" badge (this is a medium sized badge, with very small letters). That's right - the Mixolydian.

What's more, assuming that the major is the way the major is and the Mixolydian is hardly any different, then the next string (on G) of the Mixolydian is simple, it goes SEMITONE-TONE, just like the Ionian. The next bit again leads us up to the octave - and that's preceded by a minor seventh so it's got to be SEMITONE-TONE again. You have been keeping an eye on that octave haven't you? Come on, pay attention, if you've lost the key of the piece, then it's time for something like an atonal slide of the left hand and back to the riff.

(Or with the right hand if you're left handed, depending on whether you really have defied your genes and play a right-handed guitar as if you were right handed even though, in reality, as anybody who watches you eat or write will know, you're actually left handed. Some folks, of course, are in an intermediate position, and will perhaps play guitar and eat right handed - though not necessarily at the same time - while writing as a left hander. Think about this too much and you're almost bound to end up missing the cue for the next chorus, however...)

Remember two recurring themes for the Yellow Group modes?

- The Inner Pair's shorter arrangements (SEMI's) aren't split;

- There's never more than two SEMI's the same in any Yellow Group mode (theres' always a Lonely string...).

Now, to return to the matter of the Mixolydian. In the light of the above, the remaining top E for this scale is easy to extrapolate. It goes TONE- SEMITONE. Hear that Major third ring? Glad you stuck that in, eh?

the clever bit is knowing which way round the Semi's go - so, the application of knowledge you already have gives you some leverage for your grey matter to get to grips with - i.e. the Mixolydian is similar to the Ionian.

If you've been following this (and it's difficult enough for me I can tell you) it should be possible for you to simply glance at the table to see the scale and you'll have it. This is easier said than done, of course, but follow the logic, look for the pattern, observe it, trace it, test it and you'll have the scale memorised after considerably fewer practice sessions than someone who follows the inferior Path of the Parrot. And I'm hedging my bets here.

So, how about finishing off here and describing the last two scales in full? Before I do, there's just a couple of amazing facts that I'd like to draw to your attention before you trace the amazing Rotationally Symmetrical relationship between the Mixolydian and the Phrygian modes.

some amazing facts.

These facts are the

kind of thing that has helped me

trace the pattern in the modes

revealed in this scheme. They might

help you to remember as they have

helped me, and you will probably

have more to add from your own

experience.

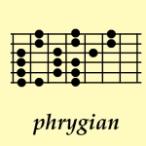

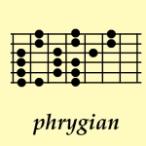

How many scales start off with that distinctive SEMITONE after the root? That sound is very familiar to many ears as being Eastern, perhaps reminiscent of Spanish guitar - play an open E major chord then a E shape Barre on 1st fret (F major). That's distinctive, right?

Only two of the modes begin like this. Instead of simply naming them, let's count down the ones we know definately do not start this way. This will make it easier to recall the ones that do.

Obviously the Ionian, and therefore the Mixolydian don't, and let's face it, the Aeolian doesn't either does it? OK that narrows it down at bit. Four modes remain. We know that the two outer modes from the yellow group have something in common - they start and end in the same way - from this we can see that because the Aeolian doesn't start with a semitone then the Dorian doesn't either. So! Three candidates left. Now, here's a clue - the central Lydian mode from the White group starts and ends TONE-TONE, so that isn't one either. So now we're left with two candidates.

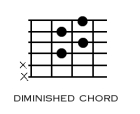

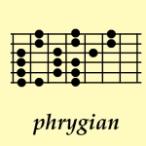

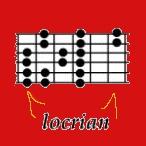

These are the Phrygian mode (the distinctive sound is war-like isn't it? Well, the Phrygians were famous warriors) and the Locrian mode. You know those diminished chords?

They're based on the Locrian. Sort of. Play the first and fifth from the Locrian up high and you'll know why that interval is called the "diabolus in musica" the devil in music. It's called the Diminished Fifth (or 'flattened' fifth). See the section below regrding cascades of similarities for the Diminished Fifth's sinister sounding cousin, 'The Augmented Fourth'.

So, there's a difference then, as well as a similarity, between the two modes that start with a semitone interval. This helps us to tell them apart. One is warlike, and the other is demonic. (Disclaimer: Please note these comments are aids to memory only and not valued judgments, and in no way should prejudice you in your attitude to these modes. Follow a Diminished chord with the corresponding Major Root chord and there's no hint of brimstone and even though the diminished chord has that 'weird' interval in it, the resulting sound evokes a happily resolved feeling for western ears. Your Statutory Rights are unaffected.)

So, anyway, we know

that these two modes start with the

semitone interval, but how do we

tell them apart? In short, the

Locrian has that bizarre Diminished

Fifth and the Phrygian doesn't. But,

this information is in addition to

something we knew already. Remember

how the Locrian was one of those

white group modes with the 4 strings

that always always always go:

TONE-SEMITONE

TONE-SEMITONE

SEMITONE-TONE

SEMITONE-TONE?

Well, there you go, then. The rest is easy: how could it be any other way? You just play those TONE-TONE's for the top two strings.

alright then, what about the Phrygian? Firstly, we can compare it with the Locrian (that starts in the same way) and continue by applying a few simple rules (that you'll be getting tired of soon as I keep repeating them) to see how it goes.

The Phrygian doesn't sound demonic, i.e. there's no Augmented Fourth (or Diminished fifth). Therefore the next string up (the A string) can't have the same arrangement same as the bass E string.

It must therefore

either go

TONE-SEMITONE or

TONE-TONE.

This is where the Phrygian's pairing with the Mixolydian comes in handy. We know that the Inner yellow pair have their 3 longer (TONE-TONE) arrangement in a block, and that the other 3 strings are not split up either. So the A string on the Phrygian must be a Semi. This allows us to define the whole of the rest of the scale. Yes! All Six strings! Just from knowing how the first string goes and applying the properties of the Inner Pair of the Yellow Group! Amazing isn't it? No? Well, maybe just a little bit intriguing at least?

Listen, given that there's an initial interval of a semitone on the E string, the A string must therefore either go TONE-SEMITONE or TONE-TONE, then in the light of the above it can only go TONE-SEMITONE then TONE-SEMITONE...then it's an easy matter of filling in the rest with those 3 TONE-TONE's.

it's those mirrors,

again.

And finally, what if

we were to define the Phrygian

without remembering a single iota

about its initial soundalike, the

Locrian, and just concentrate on the

amazing mirror image relationship

between the Mixolydian and the

Phrygian modes? Well, consider the

following...

Again, the Inner yellow pair:

- have their 3 longer (TONE-TONE) arrangement in a block;

- have their other 3 shorter arrangements (Semi's) adjacent;

- don't start in the same way as each other;

- have their mirror image nature based on both the Y axis and the X axis.

... and then flip it on the Y axis left to right, and after adjusting for the B string, you end up with the Mixolydian.

Which is a distinguishing characteristic of the Yellow group.

And is really is quite remarkable.

There are other

things I could describe, but it's

probably easier for you to just look

at the following table which

summarises the whole Yellow group.

| yellow group | DORIAN (outer) |

PHRYGIAN (inner) |

MIXOLYDIAN (inner) |

AEOLIAN (outer) |

| 3 STRINGS (TONE-TONE) | MIDDLE (EARLY) | END | BEGINNING | MIDDLE (LATE) |

| 2 STRING Identical Pair | END | MIDDLE(EARLY) | MIDDLE (LATE) | BEGINNING |

| 1 STRING 'Lonely' | BEGINNING | BEGINNING | END | END |

| 2 +1 STRING | SPLIT | ADJACENT | ADJACENT | SPLIT |

I kindly reproduce the diagrams for easy reference while you examine the above:

cascades of similarities... it appears that there are a few similarities that occur in cascades across the seven modes. They are kind of arbitary, but you may find them of some use.

Each of these are based on intervals of 4ths (third mode along):

- The Ionian and Lydian are the two member's of the White group that start in the same way;

- The Dorian and Mixolydian paired shorter arrangements of 2 strings (Semi's) both go SEMITONE-TONE;

- Next up across the scheme we have the Phrygian and the Aeolian which in contrast to the above, have their Semi's go TONE-SEMITONE;

- The Lydian and the Locrian both have the 'diabolus in musica' interval, but with the Lydian, it's an Augmented Fourth rather than a Diminished Fifth. (n.b. The Lydian is the mode with the Augmented Fourth just it just happens also to be the Fourth mode in the scheme - this might make the difference between the two modes that start with the letter 'L' seem easy to recall, but beware!; the Locrian is the seventh and not the fifth mode in the scheme. To tell these two apart it's worth remembering that the Locrian has the War-like start, and the Lydian in subtle contrast starts with the Major-sound).

- Starting now with the Dorian and the Aeolian - they both begin with the Minor-sounding SEMITONE-TONE;

- The Phrygian and the Locrian as we have seen both begin with the War-like sounding TONE-SEMITONE.

what

about the Plagal modes?...please,

if you want to invent another

obscure form of theoretical Jazz,

you're welcome, but I think I've

contributed about my fair share,

don't you?

the

landscape is now mapped but

at the end of the day, even if you

don't learn them inside-out, at

least practising the modes will get

your fingers used to working in

different ways, your ears used to

interesting intervals and your mind

might be satisfied that there's at

least a chance of remembering a

pattern rather than being daunted by

an endless array of mind boggling

dots.......

please feel free to

print this table.

Windows users' hint: Right-click on

table; Save Image As; Save; Open in

Explorer; Print using 'Portrait' orientation.

index - there's an index! Well, why not?

aeolian

and

dorian

amazing

facts

- the Eastern sound

B - String

cascades of

Similarities

central

Lydian

Hub

diabolus in

musica

diminished

chord

laws

of

mathematics

lonely

string and identical twins

mirrors

-

dorian and aeolian

mirrors

-

phrygian and mixolydian

mnemonic

(start

of explanation)

next string

up; where to go

path of the

Pattern

phrygian

and

mixolydian

table

why

learn

modes?

white Group

yellow

Group

Recommended reading: Zen Guitar by Philip Toshio Sudo.

Diatonic Scale Mnemonic. Patent Pending © 2002 James Hollingsworth. All rights Reserved.

home | gigs | music | images | more | promo | contact

© 2002 - 2024 James Hollingsworth. All rights reserved.